Last Thursday (August 18th), Le Monde, one of the largest national newspapers in France published an essay on the significance of The Cranberries’ “Zombie” to mark its 10th anniversary as a hit.

Here is the English translation, followed by the original French text:

Zombie

Le Monde / 18 August 2005

Summer Hit 1995

Let’s get back ten years ago. It is the summer and the weather is good. Suddenly, on the radio, a voice vibrates, rumbles, and roars. All at the same time, and upon a single word, haunting: “Zombie, Zombie, Zoooooooooombie…”. The sentence ends with incredible vocal performances, almost yodels, bathed in saturated electric guitars reminiscent of those of Nirvana that emerged with the grunge in 1992. That vocal assault is named Dolores O’Riordan. She is 23, has short hair, piercings lined up on her ear, a strong Irish accent and, from her 1.60 meters, she shouts to the world about the misfortune of her island and of the victims of the Ulster conflict. For a summer hit, it is as far from La Lambada as one can be.

The Irish “Troubles” theme is not new: in 1983, U2 had already sung the endless violence striking the civilians stuck between the IRA’s bombs and the British army. The famous Sunday Bloody Sunday, “non-partisan” hymn, where the drums imitate the sound of a marching drum, was recalling that “bloody Sunday” of 1972 when the British army had opened fire on a Catholic demonstration in Derry. Ten thousand people that had come to protest against the arbitrary imprisonment policy lead by Great Britain were welcome by a sustained fire killing 14.

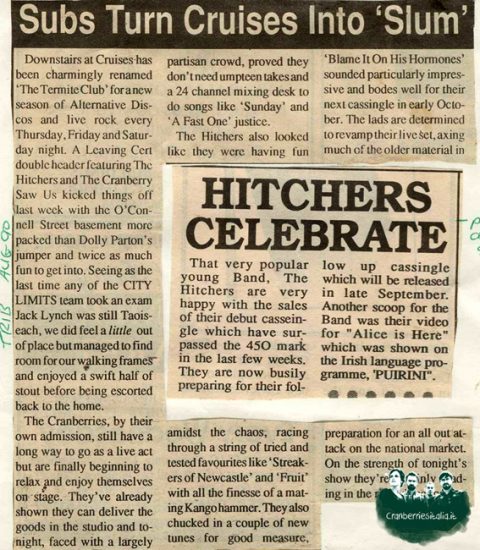

Ten years later, the Cranberries make their breakthrough on that same topic, among the “political” bands. The 20th of March 1993, they are touring Great Britain when they learn that two bombs planted by the IRA have spread terror in a commercial center in Warrington, in the north of the country. Two children have been killed – one was sitting on a bin that exploded, the other was killed the following day while he was looking for a Mother’s Day card.

The event doesn’t have the same political impact as the Bloody Sunday – which convinced Great Britain to administer Ulster directly from Westminster. However, the emotion is great in the United Kingdom. Dolores O’Riordan follows her glorious predecessor’s lead and writes Zombie: “Another head hangs lowly / Child is slowly taken / Who are we mistaken”. The song describes the inner anguish of a man – a zombie – traumatized by the civil war that lasts since the “Easter Insurrection”, date when the Republic was proclaimed: “It’s the same old theme since 1916 / In your head they’re still fighting”. The Cranberries are not very subtle. In the video, shot in Belfast, children play war in a gloomy city patrolled by armed, threatening soldiers. A divine figure (Dolores O’Riordan painted in gold) shouts her rage from the top of a cross, surrounded by scared cherubs.

Unfortunately, the song is released in 1994, when the IRA just signs a ceasefire and the civil war pauses. The singer is accused of needlessly relaunching the debate. Moreover, the song, which is meant a call for peace, comes in the media with declarations far less politically correct.

“In some cases, I am in favor of the death penalty,” Dolores O’Riordan explains to the Inrockuptibles in 1995. “In Singapore, they cut off theives’ hands and they cut off murderers’ heads. Result: no more crimes.”

She is also blamed for definitive tirades on subjects like abortion or feminism (“As far as I’m concerned, it is a thing for girls who have been ditched thirty times in their lives and decide that all men are filth”). Undoubtedly, the muse of the Cranberries, a timid teenager gone a star in a couple of months, remains marked by her childhood in the island she personifies almost caricaturely. The last of seven children, she sings in the church at the age of 5; she reads Gaelic fluently; she plays the traditional tin whistle skillfully. And, of course, she is Catholic. “At school, we had to confess,” she says. “As I hadn’t done anything bad, I had to make up sins to please the priest who was listening behind the screen. (…) But without that education, I wouldn’t have been so frustrated. And if I hadn’t been so frustrated, I wouldn’t be here today.”

Just like her, the other members of the band, the brothers Mike and Noel Hogan, bassist and guitarist, and the drummer Fergal Lawler originate from the Limerick area ; they have grown up drinking Guinness and doing small jobs. Polemics don’t prevent Zombie from going supernova. The album No Need To Argue sells more that 15 millions copies. For the Cranberries, 1995 is a sumptuous year. Dolores O’Riordan, who got married – in the church and in Doc Martens – joins her voice with Luciano Pavarotti to sing an Ave Maria during a concert for Bosnia children. A song that will belong, nine years later, to Mel Gibson’s Passion of The Christ original soundtrack. Then, Ireland decidedly becomes fashionable.

But, unlike their great predecessors, U2 or Sinead O’Connor, the bands assaulting the global market are often keen to avoid politics and polemic. The boys band Boyzone or the Corrs siblings prefer to remember their homeland’s folklore only, and barely tint their sentimental ballads with harp and tin whistle.

Claire Guillot

And here is the original French version for our francophone readers:

ZOMBIE

Jeudi 18 août 2005 / Le Monde

REVENONS dix ans en arrière. C’est l’été et il fait beau. A la radio, soudain, une voix vibre, gronde, rugit. Le tout à la fois, et sur un même mot, lancinant : ” Zombie, Zombie, Zoooooooombie… » La phrase s’achève sur d’incroyables vocalises, presque des yodles, baignées de guitares électriques saturées qui rappellent Nirvana, surgi avec le grunge en 1992. Cette déferlante vocale s’appelle Dolores O’Riordan. Elle a 23 ans, les cheveux ras, des piercings en rang sur l’oreille, un accent irlandais à couper au couteau et, du haut de son 1,60 m, elle hurle à la face du monde les malheurs de son île et des victimes du conflit nord-irlandais. Pour un tube de l’été, c’est aussi loin que possible de La Lambada.

Le thème des ” troubles » irlandais n’est pas neuf : en 1983, le groupe U2 avait déjà chanté l’interminable violence frappant les civils coincés entre les bombes de l’IRA et l’armée britannique. Le célèbre Sunday, Bloody Sunday, hymne ” non partisan », où la batterie imite le roulement du tambour, évoquait ce ” dimanche sanglant » de 1972 où l’armée britannique avait ouvert le feu sur une manifestation catholique à Derry. Dix mille personnes, venues protester contre la politique d’emprisonnement arbitraire menée par la Grande-Bretagne, avaient été accueillies par un feu nourri faisant 14 victimes.

Dix ans plus tard, les Cranberries font leur entrée, sur ce même thème, dans les rangs des groupes ” à thèse ». Ils sont en tournée en Grande-Bretagne quand ils apprennent, le 20 mars 1993, que deux bombes de l’IRA ont semé la terreur dans un centre commercial à Warrington, au nord du pays. Deux enfants ont été tués – l’un était assis sur une poubelle qui a explosé, l’autre a été fauché, le lendemain, alors qu’il cherchait une carte de voeux pour la Fête des mères.

L’événement n’a pas le retentissement politique du Bloody Sunday – qui convainquit la Grande-Bretagne d’administrer l’Ulster directement depuis Westminster. Néanmoins, l’émoi est grand dans les îles Britanniques. Dolores O’Riordan emboîte le pas à ses glorieux aînés et écrit Zombie : ” Encore une tête qui pend / Un enfant est évacué lentement / Qui sommes-nous, trompés. » La chanson décrit le tourment intérieur d’un homme – un zombie – traumatisé par la guerre civile qui dure depuis l'” insurrection de Pâques », date de la proclamation de la République : ” C’est la même rengaine depuis 1916 ; dans ta tête ils continuent à se battre. »

Les Cranberrries ne font pas dans la dentelle. Dans le clip, tourné à Belfast, des enfants jouent à la guerre dans une ville lugubre, arpentée par des soldats armés et menaçants. Une figure divine (Dolores O’Riordan, peinte en doré) hurle sa rage duhaut d’une croix, entourée d’angelots effrayés.

Manque de chance, la chanson ne sort qu’en 1994, alors que l’IRA vient de signer un cessez-le-feu et que la guerre civile fait une pause. La chanteuse est accusée de relancer gratuitement le débat. D’autant que sa chanson, qui se veut un appel à la paix, s’accompagne dans les médias de déclarations bien moins politiquement correctes. ” Dans certains cas, je suis pour la peine de mort, explique Dolores O’Riordan aux Inrockuptibles en 1995. A Singapour, on coupe les mains des voleurs, on coupe les têtes des meurtriers. Résultat : il n’y a plus de crimes. »

On lui reproche aussi des tirades définitives sur des sujets comme l’avortement ou le féminisme (” Pour moi, c’est quelque chose pour les filles qui se sont fait plaquer trente fois dans leur vie et qui décident que les hommes sont tous des ordures »). Sans doute l’égérie des Cranberries, adolescente timide devenue rockstar en quelques mois, reste-t-elle marquée par son enfance dans son île, qu’elle incarne jusqu’à la caricature. Petite dernière d’une famille de sept enfants, elle chantait à l’église dès l’âge de 5 ans ; elle lit le gaélique dans le texte ; elle maîtrise le tin whistle, la flûte traditionnelle. Et, bien entendu, elle est catholique. ” A l’école il fallait toujours se confesser, raconte-t- elle. Comme je n’avais rien à me reprocher, j’étais obligée d’inventer des péchés pour faire plaisir au prêtre qui m’écoutait derrière la grille. (…) Mais, sans cette éducation, je n’aurais jamais été frustrée. Et si je n’avais pas été frustrée, je ne serais pas ici aujourd’hui. »

Les autres membres du groupe, les frères Mike et Noel Hogan, bassiste et guitariste, et le batteur Fergal Lawlern sont comme elle originaires de la région de Limerick ; ils ont grandi en vivant de Guinness et de petits boulots. Les polémiques n’empêchent pas Zombie de faire le tour du monde : l’album No Need to Argue s’écoule à plus de 15 millions d’exemplaires. Pour les Cranberries, l’année 1995 est fastueuse. Dolores O’Riordan, qui s’est mariée – à l’église et en Doc Martens -, joint sa voix puissante à celle de Luciano Pavarotti pour chanter un Ave Maria lors d’un concert en faveur des enfants de Bosnie. Une chanson qui figurera, neuf ans plus tard, sur la bande originale du film La Passion du Christ, de Mel Gibson. Puis l’Irlande devient décidément à la mode.

Mais, au contraire des grands anciens, U2 ou Sinead O’Connor, les groupes qui se lancent à l’assaut du marché mondial sont soucieux d’éviter politique et polémique. Le boys band Boyzone ou la tribu des Corrs préfèrent ne retenir de leur patrie que son folklore, et se contentent de teinter leurs ballades sentimentales de harpe ou de pipeau.

Claire Guillot

Thanks to Sir Thomas Montagné, Esq., for the scan and laborious translation.

Source: Le Monde (France)