We received some feedback that some of our visitors weren’t quite able to read the scans taken from this weekend’s Sunday Independent, so we took a little bit of time to type of the entire article, below. Certainly an excellent read, so make sure you get through it all!

Berried treasure

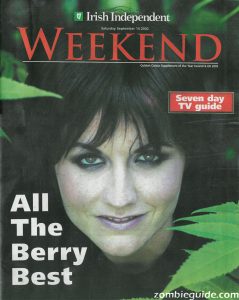

The biggest Irish rock band since U2 are celebrating the 10th anniversary of their debut album with a global tour. The Cranberries, still friends, still three lads and a lass from Limerick, have sold over 38 million albums. But next year they’re taking time out. Barry Egan met up with them in Milan.

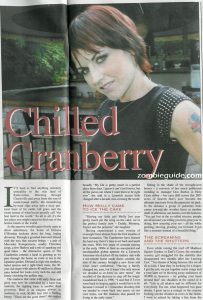

THE disguise works a treat. No one recognizes her. Not even the security guard who block the superstar’s path to her own show. There are no stampy-feet hissy-fits. She manages a laugh until one of the tattooed brick- shithouses on patrol comes to his senses.

He realises that the elfin figure in the shades with the baseball cap pulled down over her face is actually Dolores O’Riordan — one of the reasons why 20,000 people are queuing up outside a giant venue in Milan tonight as the pouring rain rolls off the Alps.

O’Riordan was bored hanging around the drab hotel in the italian city and walked up to the venue on her own. She wanted instead the sanctuary of her own dressing room, a world of scented candles, sumptuous cushions and coming colours. It is in here that Dolores disappears.

Before a show she has a routine of Reiki, a massage and yoga. However, beneath all that Eastern calm, Dolores is desperately missing her two children. She’s chartering a private jet to be home for her son Taylor’s birthday on Saturday. Thirty thousand euros. Worth every cent. Giant balloons are being inflated and clowns hired. (Editor’s note: We hope Mickey the Clown is not among those invited.)

“He’ll never be five again. I don’t care about the money,” she says. “I’m a mother more than I’m a rock star.”

After the birthday bash in Kilmallock, her home in Co Limerick, Dolores is due to fly back to Italy the following day for a show in Trevisio, then move on to Strasbourg, Brussels, Amsterdam, Glasgow and London. In the past 48 months, the band have performed in 30 countries around the world. It is non-stop. Or at least it was.

Come January, the Cranberries are taking a year off. O’Riordan is taking some long-overdue time out. Being on tour for long periods, she misses Taylor and baby daughter Molly like crazy.

“We were asked to go to Asia in January but I couldn’t,” she says before the show. “You miss them growing up. You’ll never have that back.”

The year 2003 is Dolores O’Riordan’s year for being mammy again. She also has plans to take acting lessons and maybe do a movie if the right part comes along. “But then maybe I’d be f**king crap!” she laughs. (She was offered a part in Titanic but turned that down flatly — and the offer to write some music for the film.)

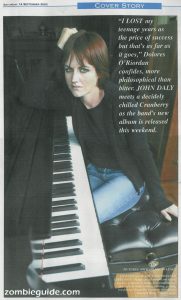

She would also like to record — at home — an album of left-of-centre songs. She played a snatch of just such a number behind the big white piano at soundcheck earlier in the day: it is ethereal, surreal, sad, beautiful and trance-like. And decidedly unlike anything we’ve ever heard Dolores play before.

“We were in school when the Cranberries took off, so that’s all we’ve ever known,” she says later. “We’ve never really fully experimented and tried different things.”

Meanwhile, guitarist Noel Hogan is running the London marathon in April next year. (He runs 15 miles every second day.)

“And I…” begins his brother, Cranberries bassist Mike, “…I’m going to have another sex change next year.”

“I can just imagine you in a wig and women’s underwear!” says drummer Fergal Lawler.

Dolores doesn’t have to imagine. She can recall the early days of the Cranberries when the brothers Hogan would break into her room, liberally applying her make-up before helping themselves to their singer’s undergarments.

Like two gaelic Danny La Rues, Noel and Mike would then appear on the tourbus imitating the two girls, young Dolores and her good friend Brefni. “They used to bust my bras and knickers all the time!” Dolores remembers as Mike and Noel look on horrified that their secret’s finally out. There I was minding my own business when suddenly the two of them would run down the bus in my underwear and plastered in lipstick.

Another night, after traveling up in the back of a bread van from Limerick for a Dublin show, Dolores and the band, desperate for digs, stayed in accommodation in Mountjoy Prison. (Relax: Dolores’s brother works there.) Apparently the brothers Hogan found loads of women’s clothes in the hot- press in the ‘Joy and once again dressed up to take the mickey out of their young singer.

They can all laugh about it now, the days of having nothing. They can remember the early days when Dolores was dating (“nothing serious”) Liam O Maonlai of the Hothouse Flowers, and the times the unknown Limerick band played the support slots to the then hugely popular Dublin band. Starving, the male members of the Cranberries would pester Dolores into getting food from her boyfriend’s band’s dressing room.

“The Hothouse Flowers have very nice cheese,” Mike, Noel, and Fergal would say. “Get us some!”

“Leave me alone!” she would reply. “I’m not scoring cheese off my boyfriend for you!”

“We were the bummer opening act,” Fergal remembers now. “We had nothing. No food. No drink. No prospects. And no cheese!”

Ten years on, dairy products are no problem for the biggest rock band to come out of Ireland since U2. (Their opulent, cheese-filled dressing room is a testament to this.) The Cranberries, still friends, have sold over 38 million albums. They are known right around the globe.

Closer than ever, their trust, loyalty and friendship remain incalculable. They also have a shared, out-of-kilter sense of humour of people who have spent years living in each other’s pockets.

Dolores tends to begin anecdotes with a[n] anxiety-inducing “He’ll kill me for this,” before dredging up the time Fergal drank a bottle of local tequila in Mexico in 1997, complete with the worm inside the bottle and some ants’ eggs, before “throwing up for hours.”

Unfortunately for the Cranberries, the next morning they were brought like visiting dignitaries to see a local attraction. Somewhat the worse for tequila and wine, a day in the baking hot sun was not what their fragile Limerick systems needed.

“Our throats were like someone had poohed in them,” says Dolores. “We were all dying of hangovers. This religious Indian guy, who took peyote every day, kept trying to get us to chant, but all we wanted was water. He gave us names. I was Snake.”

Another night, after a binge in an English country pub, the band were cycling back to their posh hotel when Dolores’s husband Don fell off and lay prostrate on the ground. Once she got him back to the hotel, Dolores, in search of some life-giving elixir, slipped her tiny hand in behind the locked bar downstairs and managed to turn the key. Drinks for everyone.

“You have to be a bit naughty sometimes,” she says. “One of the great things is, it’s still fun being in the Cranberries. And if it stops being fun, you should stop doing it. It would ruin it. Because we’ve been there before, when we almost became a commodity. We were like four basket cases freaking out of our heads all the time. “How many panic attacks have you had today?”

Panic attacks are very much a thing of the past. They are now celebrating the 10th anniversary of the release of their debut album, Everybody Else is Doing It, So Why Can’t We?

It all started in May 1990: a[n] 18-year-old Dolores Mary O’Riordan turned up at the Hogan’s house with a keyboard under her arm to sing Linger. Within three years, the Cranberries had achieved staggering success in America and the UK. The massive stardom hasn’t overpowered Dolores to the extent that she has withdrawn from public life. You still occasionally see her around the clubs of Limerick.

“We don’t think of ourselves as stars,” she says. But they are. Bigger than a thousand Pop Idols put together.

Growing up in Limerick, and still living there, has stopped the band from ever getting big heads, says Fergal. “Irish people slap you down if you start getting too big for your boots,” he laughs.

The path to fame is not always an easy one. Those whom the gods wish to destroy are granted fame and fortune at a dangerously early age, they say. And the Cranberries were but babies. They survived where others before them perished. “When you become famous very young — when you become a millionaire almost overnight — people expect you to be screwed up,” Dolores says. “So it makes you more determined to keep your life together. It makes you more determined to make the simple things in life right.”

Like?

“Like a good marriage,” she says. “Having children. Being a good parent.” Keep your marriage together. Staying loyal, and seeing the big picture. And not getting caught up with the small, quick temptation, or whatever.”

Dolores and Don Burton, Duran Duran’s former tour manager, were married in 1994 in Holy Cross Abbey outside Tipperary. (Noel’s wife is Catherine, his brother Mike is married to Siobhan and Fergal’s wife is Laurie.) They seem blissfully happy together. Tonight in Milan, Don buzzes adoringly around her all evening. She dotes on him in return, hugging and kissing him at every opportunity.

On the tourbus later, she recounts affectionately how her husband is like an animal in bed. Snores like an animal, that is. To illustrate her point, Dolores reaches over and demonstrates how she holds his nose, but even that doesn’t stop him, it seems. When he finally stops, baby Molly will invariably wake up in the other room.

Earlier, while Dolores held 20,000 Italians in thrall for two hours, Don brought me up onto the side of the stage where he gushed with the praise of the truly in love: “That’s my wife! And she’s the greatest singer in the world!”

From the reaction of the crowd to Dolores’s vocal dynamics on Dreams, Linger and Zombie, there are plenty of people who agree with his assessment.

Don’s relations from Canada are over for the show. While his wife gets changed for the night’s main entertainment in her dressing room, Don orders pasta and steak for everyone, and, in the backstage dining area, holds court: outlining the special freedom of riding his horses bareback on their 250-acre ranch in Kilmallock (it makes the Ewings’ South Fork look like an afterthought). He says proudly that their children get up on horses like sitting up on a chair.

He charms everyone. Well over six foot, with spiky blond hair, he reminds me of nobody so much as Fachtna O Ceallaigh, Sinead O’Connor’s former boyfriend, about who she sang Nothing Compares 2 U. When I comment on the similarity, Don tells me about the occasion a long time ago when Sinead sat down on his knee — platonically, of course. Until Don’s future wife noticed that he was being used as an armchair and said: “Grrr!”

TONIGHT, Dolores runs around the stage like Penelope Pitstop on tequila. For other reasons, it must be exhausting being Dolores. Everybody wants you. Even the Pope. She will make a solo appearance at the Vatican’s Annual Christmas Concert in Rome on December 14.

Last year, she sang for His Holiness with the Vatican Orchestra (and Westlife — Dolores and Don’s son Taylor has Westlife on the side of his lunchbox. Dolores bought it for him.)

“Don is not Catholic — he’s atheist or heathen or whatever you call it, he was never baptised — but when he met the Pope, he was moved,” O’Riordan recalls. “The Pope’s presence is amazing! He is so old but is still rocking at his age. And he’s bigger than the Rolling Stones!”

The Cranberries can’t wait to be home for Christmas. Noel Hogan will have a double celebration. He was born on Christmas day, 1971. “My dad was pretty pissed off,” he says, “because there weren’t any pubs open on Christmas day in 1971 to celebrate.”

Dolores will be bringing Taylor to midnight mass for the first time. “At the age of five, Taylor and kids his age start to become really aware of Christ. Thankfully, at school the heavier elements of the catechism for children have been taken out. When we were kids we learnt about burning in hell and the devil. That is gone.”

None of the Cranberries are practicing Catholics but they all bring up their children in that belief system, because, says Fergal, “You should give your child some identity, and then when they’re older they can choose.”

Churches have a special potency for Dolores. When she was 15, she played the organ at mass in Ballybricken. The choir ranged in age from 35 to 75, she remembers. “It was like my youth club. I learnt a lot of good things — like Latin and hymns.”

At school in Laurel Hill in Limerick, Dolores used to play camogie. He legs were permanently black and blue from the wallops she got on the field but that only seemed to embolden her. She and another girl were the only two in a class of 35 who played camogie. The other 33 girls played hockey.

Dolores hated hockey. It was, she says, for posh sissies. You had to wear culottes. “I wanted to wear shorts and socks and push and shoulder and shove like the boys.”

Stuff patriarchy! Give me those hurleys now!

Twentysomething years later, the same girl emerges from the dressing room at nine o’clock, a glamorous Dolce e Gabbana goddess. The crowd greets her appearance onstage like the arrival of gladiators in ancient Rome. Noel and Mike Hogan and Fergal and Dolores play like their lives depend on it.

Afterwards, beyond the security guards at the backstage door, hundreds of fans have waited patiently in the rain for a glimpse of their idols. Genuinely shy, Dolores sees the crowd and asks me whether I think she should go out or not. I tell her that they love her. Soon Dolores is shaking hands and giving autographs for the multitudes.

“Ciao, Dolores! Dolores! Brava Dolores!” they shout.

Fifteen minutes later the object of their devotion is inside her state-of-the- art tourbus, opening a bottle of wine and contemplating the nature of her existence. She knows God’s existence is as impossible to prove as it is to disprove. But she knows there’s something else after death. She views her life as being like river water, gushing over rocks to begin with, later flowing wider, and finally merging painlessly with the sea, losing its individuality but continuing as part of the greater whole.

On tour in Turkey in mid-November, Dolores recalls waking up at dawn to prayers being chanted from the mosques. After the concerts, the Turkish fans gave Dolores presents of decorative eyes that, they said, kept watch to keep evil away.

“I have a big collection of eyes,” says the green-eyed chanteuse. “That’s the great thing about traveling the world: you realise how similar a lot of religions are.”

She tells me about her lucid dreaming — crashing on planes into bunkers then waking up still on the plane. Freud wouldn’t get a look in.

Dolores, who turned 31 last year [sic], says she appreciates life more than she used to. “I’m more impulsive. Instead of talking about things, I just do them. I trust my own instincts, I’m a little bit more connected with the spirit. That is one of the good things about getting older. Gravity kicks in, yeah, but there are better things than the visual.”

One of Dolores’s earliest memories is being about five at school in Limerick. The headmistress brought her out of the class and up into the sixth grade class where the 12-year-old girls were. She sat Dolores up on the teacher’s desk and told her to sing for them. The five-year-old loved it — singing was something she had “that could win people over.”

Tonight in Northern Italy more so than ever.

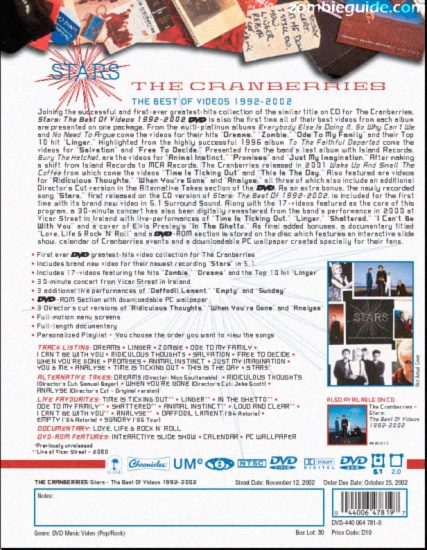

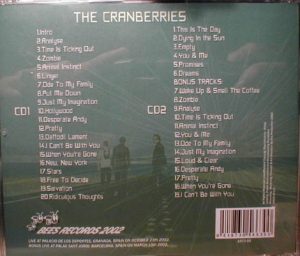

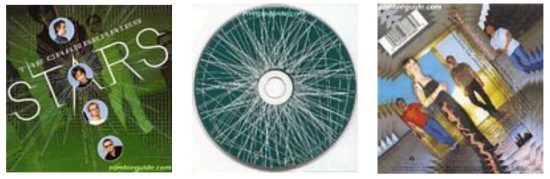

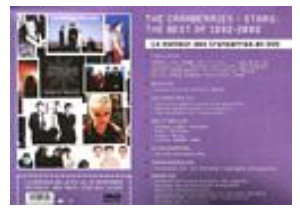

The Cranberries play the Point in Dublin on December 6, 2002. Their album ‘Stars — The Best of 1992-2002’ is now available.

Source: Exclusive

The videos for “Uncertain” and the original version of “Dreams” are absent from the new DVD

The videos for “Uncertain” and the original version of “Dreams” are absent from the new DVD